Klaassen & Magnus's 22 Myths of Tennis— Myth 12

21 May 2016In this week’s Beyond the Baseline preview to the French Open, Jon Wertheim called the women’s draw from spot 2 down “all over the place”. With only 2 2016 clay court titles among the top 4 seeds on the women’s side and Serena Williams without a major title since last year’s Wimbledon, it’s looking like anyone’s guess over which WTA player will walk away with the Roland Garros title in two weeks.

Many in the tennis world have argued that men’s tennis is more competitive than women’s tennis. But does the chaos we’ve seen on the women’s side this year turned that idea on its head? How would one even go about try to judge what it means for a tour to be “competitive”, anyway? This is exactly the challenge Klaassen and Magnus take on in the next of their 22 myths of tennis.

Myth 12: “Men’s tennis is more competitive than women’s tennis”

With myth 12, K&M turn to the perennial question of the relative competitiveness of the men’s and women’s game. In Analyzing Wimbledon, they conclude that the men’s game is more competitive and use two arguments to back up their conclusion. Their first strategy looks at the frequency with which the top 16 seeds at Grand Slams have made it to their expected round (the Round of 16). In other words, its a criteria that is essentially tied to upsets at Grand Slams. Their logic is that more upsets corresponds to a stronger field.

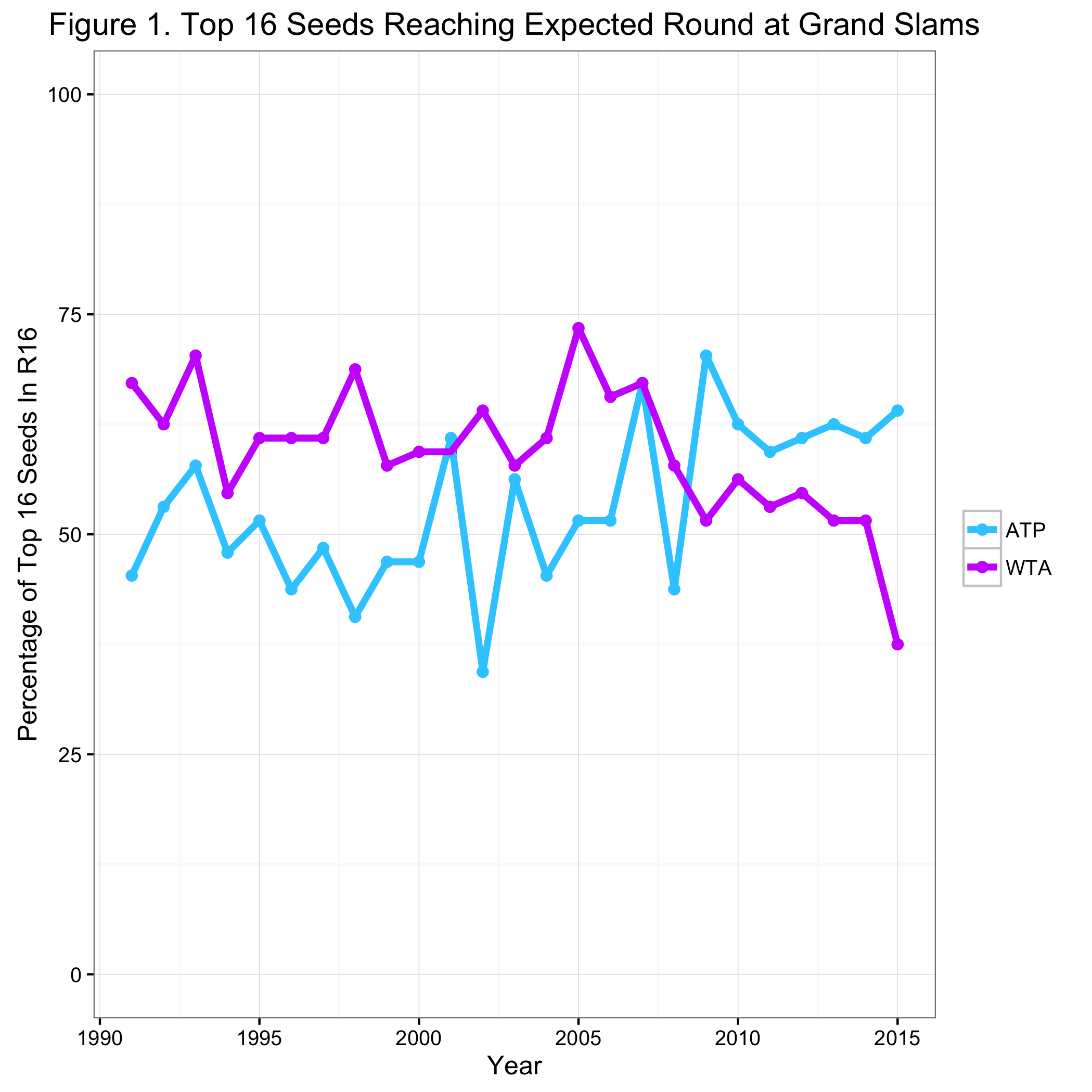

When K&M look at the frequency of top 16 upsets from the 1990s to 2012 they find that most of the years have had more of the top 16 women advance than the men. This argues for a stronger field on the men’s side. However, if we look at the past 5 years (Figure 1) we see that the relationship has reversed. During this period about 60% of the top 16 men have reached the round of 16, while the corresponding percentage for the women has been closer to 50%.

We could say, at this point, that K&M were right but the story has changed for the current generation of players. Then again, it might be that using upsets of the top 16 seeds to just weird way to measure tour competitiveness. Seeds aren’t a perfect measure of player ability and comparing men’s and women’s upsets at the Grand Slams isn’t really a fair comparison because of their differences in match format: men playing a best-of-5 and women playing a best-of-3. Myself and others have already shown that the role of match format is huge and makes any Slam-only gender comparison questionable.

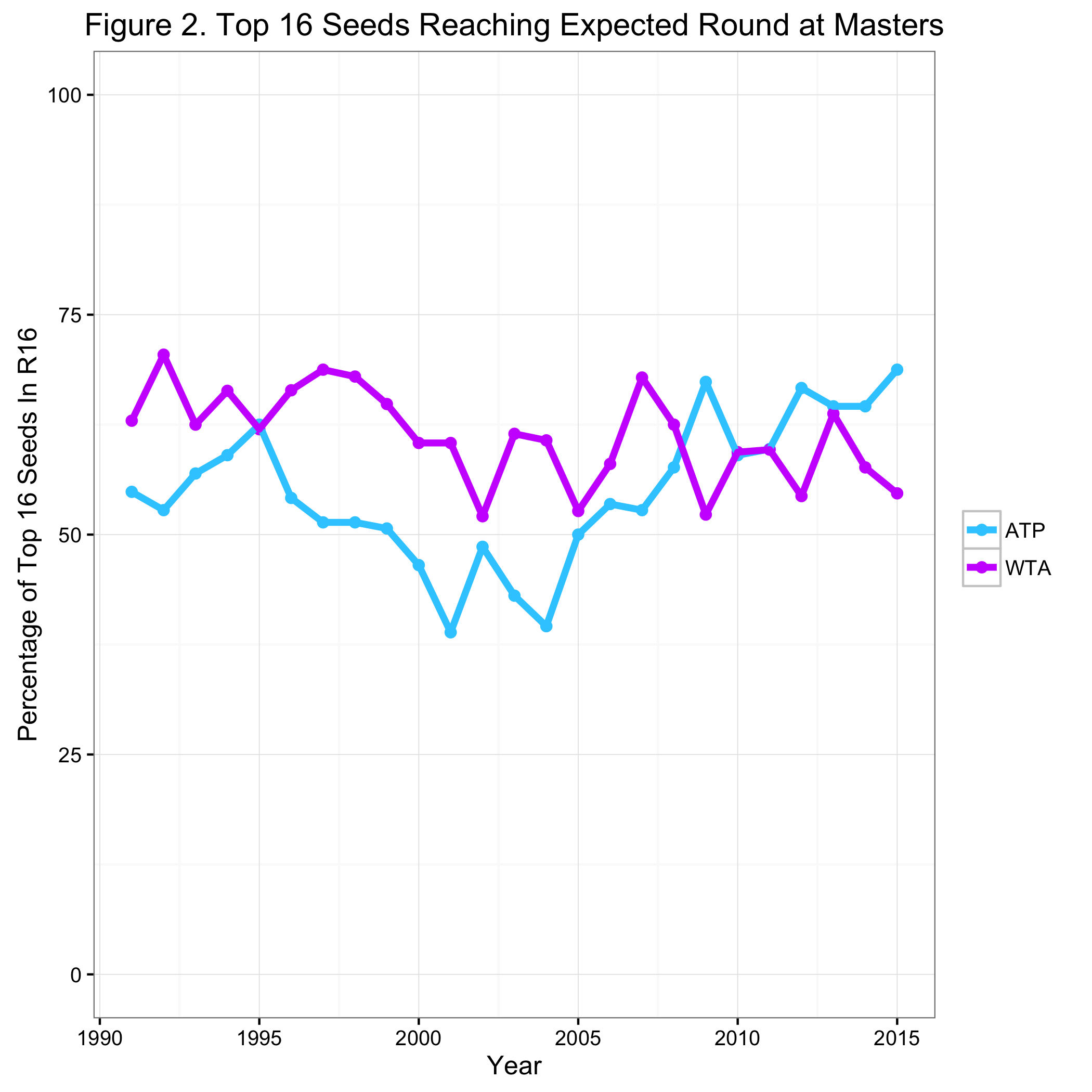

We can see this by applying the same analysis to the next highest tier of tournaments (Masters, for men, and Premier-level and above, for women) where both tours play a best-of-3. We see (Figure 2) that there is much less of a gap between the tours and “competitiveness” has gone back and forth over time in an apparently random fashion.

Better Measures of Player Quality

When we think about competitiveness, in all comes down to prediction. If a tour’s field is deep, we should struggle to predict match results. So the more we are finding matches to be a “toss up”, the stronger the competition on the tour.

To predict match outcomes well, we have to know about each player’s current ability and how well their skills match up against each other. Neither seeding or ranking getting at either of these very well. So any arguments about tour competitiveness that are based on player ranking are fundamentally flawed because they assume that ranking, as a measure of player quality, is “good enough”.

K&M’s second argument for the competitiveness of the men’s tour makes this mistake because they use the association of the difference in player rankings, between the two players in a matchup, and probability of winning on serve to say which tour has the greater depth. I think we are on solider ground if we use Elo to measure player quality.

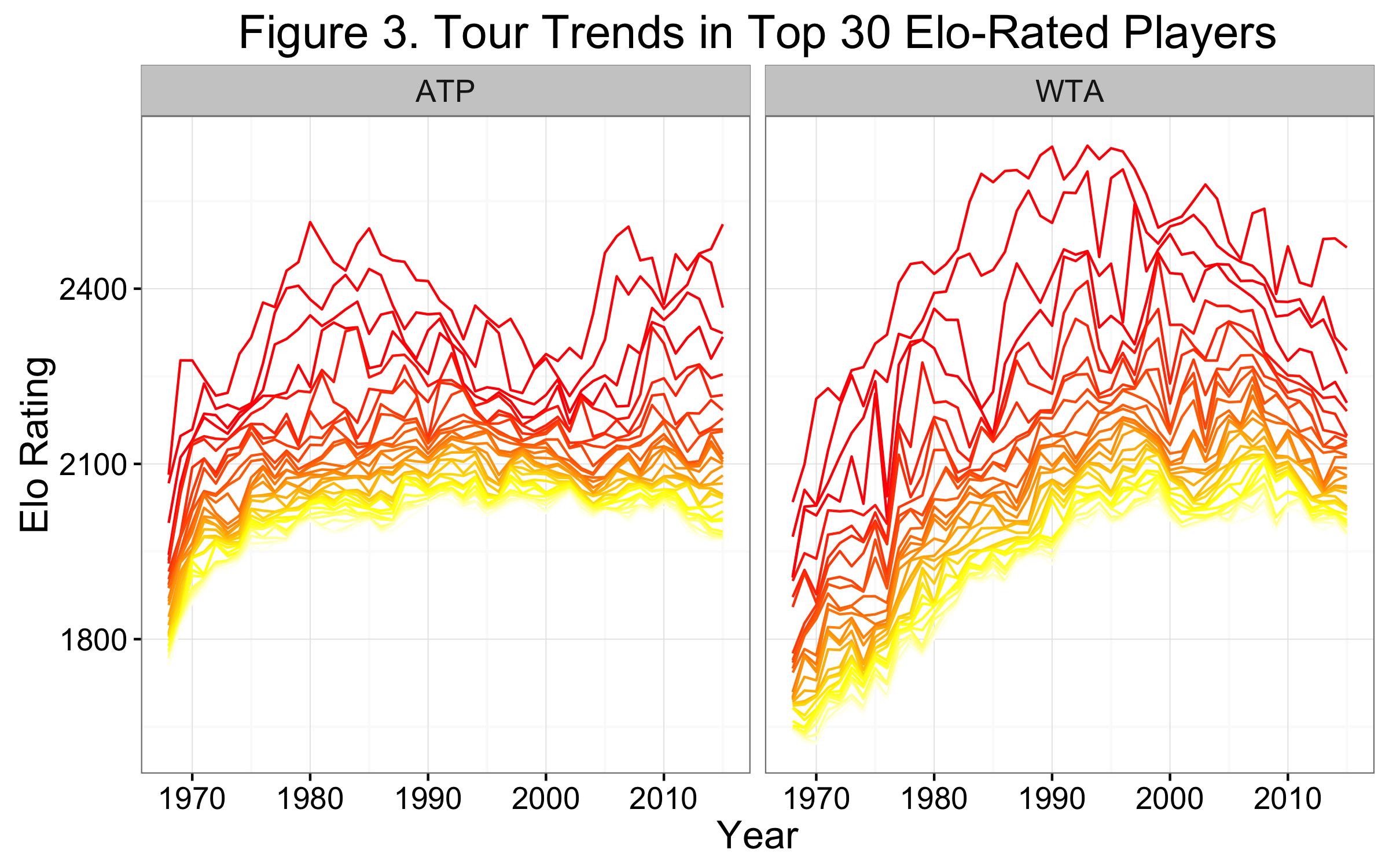

Because the difference in two players’ Elo ratings tell us about the likely outcome of the match, charting the relative magnitude of Elo ratings over time gives us a picture of the depth of a tour. The more “squishiness” among the Elo ratings of the top players, the more it reflects a tour with a lot of depth, where any match is going to be a close call. The more spread out the Elo ratings, the more predictable the tour.

If we look at several decades of Elo ratings for the 30 players who had the peak Elo ratings in each year, we find some interesting patterns on each tour. Before the mid-2000s, the men’s tour had a tightly packed group in terms of quality, especially in the transition period between the Agassi-Sampras era and the era of the Big 4. The women’s tour during the same period showed much less strength in the bottom half and the most highly-rated players clearly separating themselves from the rest of the tour. But in the past decade, the women’s tour is looking increasingly like the men’s tour, in terms of the spread in Elo ratings. And from the looks of the last few years, it seems that both tours are equally competitive at the top of the game.

The important thing to take away from all of this is to realize how dynamic the idea of competitiveness of a tour is. When reading the write up of K&M on this topic, it sometimes seemed that they were talking about some intrinsic, fixed characteristic of the tour. In reality, we shouldn’t be asking which tour is the most competitive but what does the competitiveness of the tours look like right now?

Competitiveness Versus Consistency

This whole discussion of male and female competitiveness in tennis brings up an interesting irony. If competitiveness is all about the unpredictability of the tour, it should be the flipside of consistency–as the more consistent the top players are the easier it is to predict outcomes.

Still, the tennis world (and even K&M sadly appear to have fallen into this trap) seems to want us to believe that the men’s tour is not only more competitive than the women’s tour; it’s more consistent too. How can they have it both ways? Either commentary on the game needs to get clearer about its terms or commentators need to recognize that, in this respect, they aren’t being fair to the women’s tour.

If you liked this story, share it with your followers or follow this site @StatsOnTheT on Twitter.