Klaassen & Magnus's 22 Myths of Tennis— Myth 16

25 Jun 2016Britain’s decision to Brexit will inevitably make for an unusual backdrop at the 2016 Wimbledon, which gets underway this weekend. But with a packed draw and stadium roofs to combat uncooperative weather, we can still expect the next two weeks to bring us some unforgettable matches and headline worthy moments.

One story many of us will be keen to follow is whether American Coco Vandeweghe can continue her impressive run of grass court wins on the grand slam stage. Taking the title at the Rosmalen Grass Court Championships (in ‘s-Hertogenbosch) and reaching the semifinal at Birmingham (the WTA Aegon Classic), Vandeweghe has had a series of impressive wins during her warm up to Wimbledon. Her performance in the third set of her victory over No. 3 Agnieszka Radwanska forced us all to stop and take notice. In the second point of the fourth game, Vandeweghe hit a streak, winning the next seven points and earning a triple break opportunity. Vandeweghe eventually won that break and followed it up with two more breaks to win the match in a decisive 6-3 final set.

Vandeweghe’s dominance in the third set of her defeat of Radwanska was a classic example of a player who appears to be in a “winning mood”. This is Klaassen and Magnus’ favorite term for what most sports call the “hot hand”. Different labels but both refer to the same phenomena of players performing better when they are in a winning streak than when they are not.

With myth 16 of Analyzing Wimbledon, K&M look to see if a winning mood has an effect on the risks player take when serving.

Myth 16 “Players take more risks when they are in a winning mood”

K&M test risk-taking under a winning mood on serve by looking at how winning the previous point is related to the frequency of first serves in and double faults. In both analyses, they find evidence that greater risk taking (fewer serves in) is more likely when a server has won the previous point.

These findings are interesting but, if we really want to look at the effect of winning streaks on performance, we need to look at more of the history of a match than just the outcome of the previous point. A more comprehensive summary of a player’s “streakiness” in a match is their set point spread.

At any time in a set, the set point spread is the difference in the player’s points won minus their opponents points won in a set. I put “streakiness” in quotes, because a big positive number in the set point spread doesn’t mean that the player had to win those points consecutively. Still, because of the hierarchical nature of points in tennis and the server’s advantage, consecutive wins is too high a bar and I think point spread is a better summary of a player’s sense of being on a winning tear.

Revisiting Myth 16

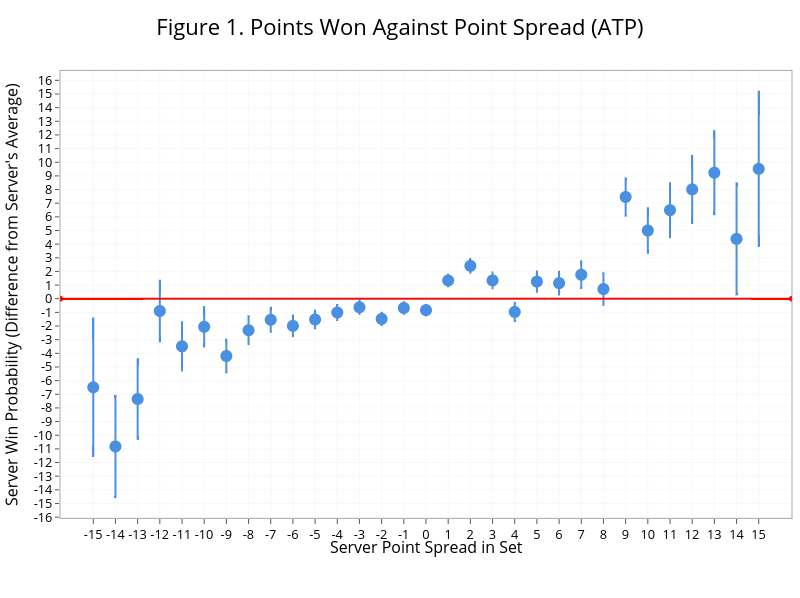

Figure 1 shows how a positive and negative point spread affects a server’s chance of winning a point. The data in this plot comes from all ATP matches at grand slams between 2011 and 2015. The y-axis shows the effect in terms of the change in a player’s average percentage of winning on serve. So a zero (in red) would mean no change.

This plot shows us effects of both a winning and losing mood that is roughly linear. That is, as the server’s point spread increases there is a coincident rise in their performance in future points. However, the opposite happens when they get behind in the score. The magnitude of the effect implies a 1 percentage point increase (decrease) for every gain (loss) of 4 points in the point spread.

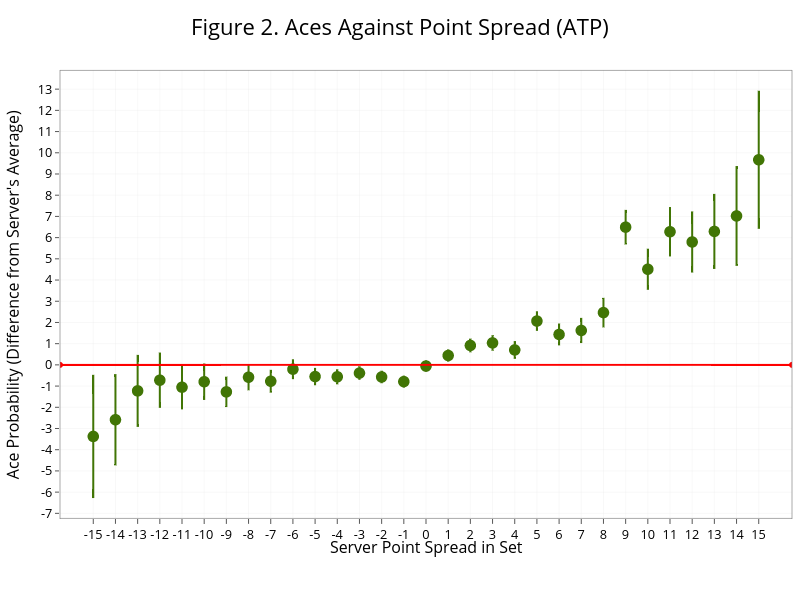

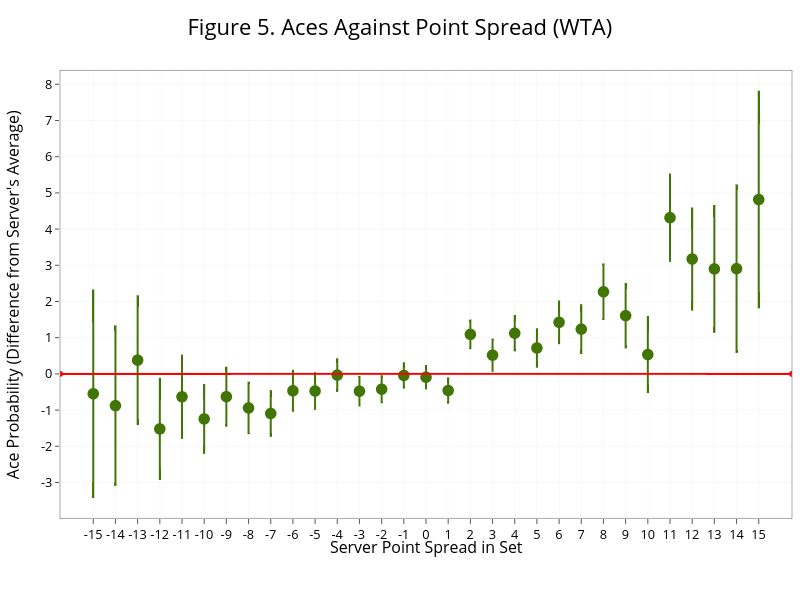

The previous figure focuses on the role of a winning mood on the overall chance of winning a point. But myth 16 is concerned with risk-taking on serve. To get at that question, we look at the relationship between point spread and the frequency of aces. Figure 2 shows the results of this analysis and reveals a similar finding as was found for point wins. The frequency of aces goes up when a server is ahead in the point spread (1 percentage point for every 5 points gained in point spread). One difference with point wins is that aces appear to be less affected a negative point spread, though this could also be due in part to servers running up against the strict lower bound of zero.

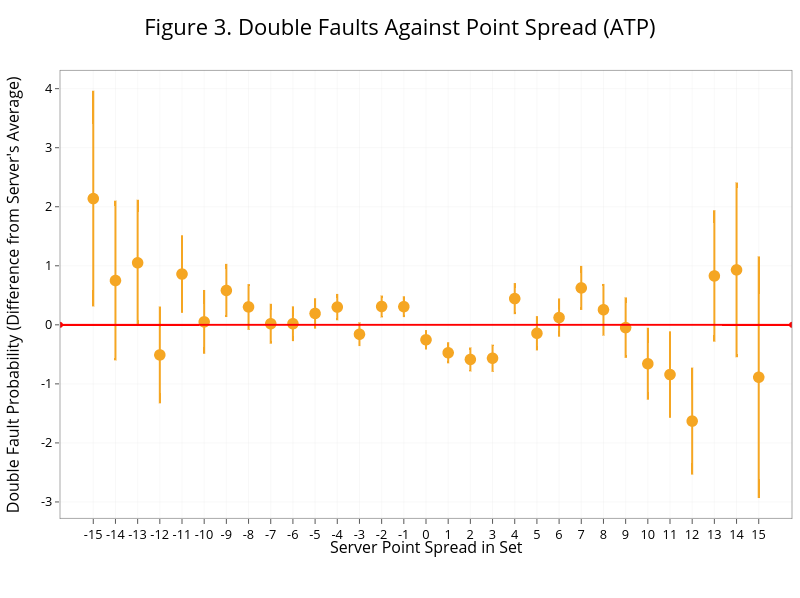

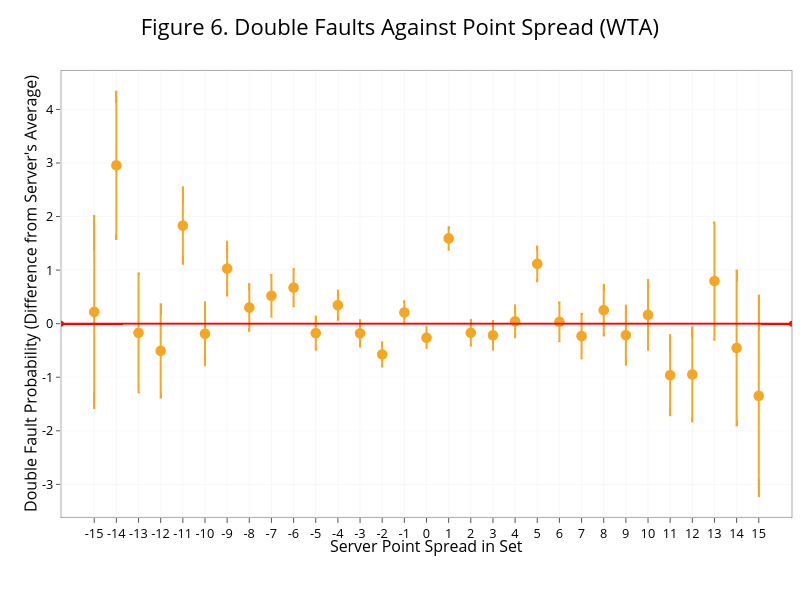

When we turn to double faults (Figure 3), there is no evidence of a winning mood effect. Servers appear to go for bigger first serves win ahead and for safer first serves when behind but they may keep to a fixed strategy on second serve risk-taking no matter the score.

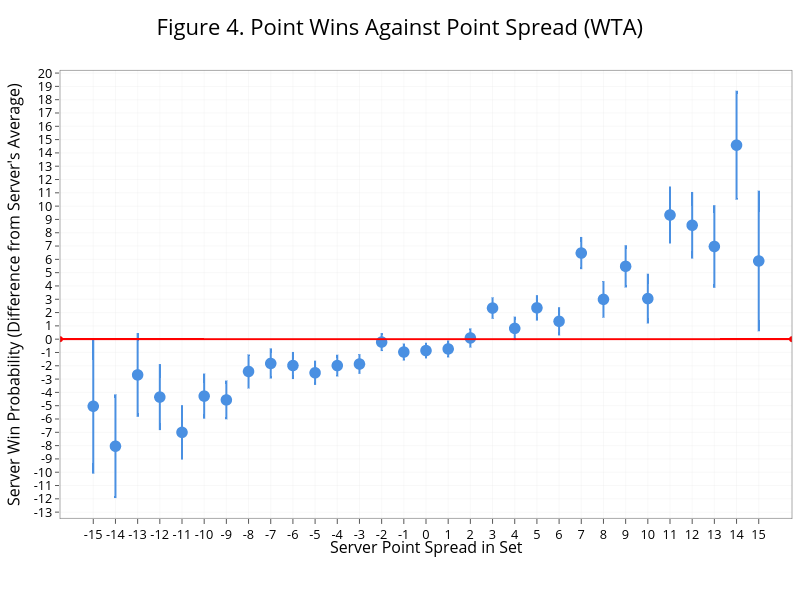

Figures 4-6 give the corresponding winning mood effects for the WTA based on the same years of grand slam point-by-point data. They show the same relationships as found for the ATP. Point spread is positively correlated with winning on serve and the frequency of aces but is unrelated to the frequency of double faults.

Summary

Point spread is an infrequently reported stat in tennis, which is too bad because it looks to be an important indicator of when a player could be performing under a hot hand or having to perform against one.

All the point spread analyses in this post confirm K&M’s conclusion that players take more risks on first serve when in a winning mood. The cause of this effect is still an open question.

Do aces go up because a server on a winning streak, buoyed by their lead, is going all out on first serve? Or does a receiver who is behind in the set have less of a will to stretch for the more difficult serves? Wimbledon will give us an abundance of matches to try to find our own answers to these questions. I know I will be looking particularly at the choices servers are making on first serve coming off a break of their opponent (a gain in point spread) to see if a winning mood makes an appearance.

If you liked this story, share it with your followers or follow this site @StatsOnTheT on Twitter.