Klaassen & Magnus's 22 Myths of Tennis— Myth 21

30 Jul 2016July has been a stellar month for British player Johanna Konta. After defeating one of her idols, Venus Williams, to win a Premier title at Stanford, Konta will play today for a spot in the semifinal of the Rogers Cup.

This month, Konta just can’t seem to lose. When players hit a streak like Konta has, it can sometime seem like winning becomes inevitable, as if with each win added to their record the next win becomes even more likely.

This kind of “rich get richer” effect goes by various names in sport: hot hand, streakiness, momentum, etc. The name Klaassen and Magnus like to use to refer to this effect is a winning mood.

For this week’s myth, K&M take a look at the existence of a winning mood within a match in tennis. In other words, is the kind of streakiness we see in Konta’s July run something that we also find for point wins in a match?

Myth 21 “Winning mood exists”

One of the main takeaways K&M stress when talking about a winning mood is that the phenomenon can be defined in a variety of ways. Is winning in straight sets an example of a winning mood? How about winning 10 points in a row?

Given the variety of choice, K&M use two different approaches in Analyzing Wimbledon to test whether a winning mood for points exists in tennis. First, they consider whether winning the previous point makes it more likely that a player will win the next. Second, they ask whether the frequency of winning the previous 10 points on serve (effectively 2 service games) has an additional effect beyond the outcome of the previous point. In each case, a positive correlation with either the previous point outcome of the win percentage of the previous 10 would be an indication of a winning mood.

Since a player’s quality will obviously be associated with the outcome of the previous service point and the frequency of wins on the previous 10 service points, K&M adjust for the ranking difference and sum of the rankings of the two opponents in the match. After all is said and done, they found a winning mood associated with the outcome of the previous point but not the 10-point average.

Revisiting Myth 21

A few weeks ago, I looked at the concept of a winning mood in relation to risk-taking on serve. There, I used point spread to summarise a player’s winningness up to the current point in a set. The point spread is simply the difference in how many points the current server has won in the set compared to his or her opponent. I like this way of summarising a player’s winningness because it avoids an arbitrary point cutoff but, by restarting at the beginning of each set, it is still sensitive to what has happened in recent games.

Now, we know that points won in a tennis match can look pretty close, even when the set score looks lopsided. So how much can we expect a point spread to differ from even?

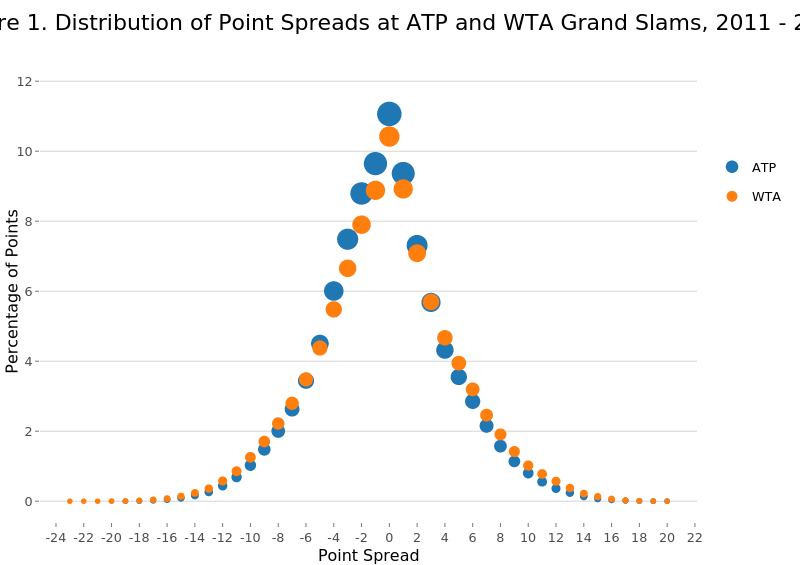

Using 2,000 ATP and WTA grand slam matches, Figure 1 shows the distribution of point spreads. Points are scaled relative to the total points in the sample when the given point spread occurred, giving a sense of the rarity of the extremes. We find that it wouldn’t be out of the realm of possibility to see point spreads from -20 to +20. We also see that the ATP and WTA distribution of point spreads are largely similar, the WTA having a lower frequency of even spreads.

Since we have found that the point spread can vary substantially over the course of a set, the next immediate question is whether player’s perform differently when the point spread increases or decreases?

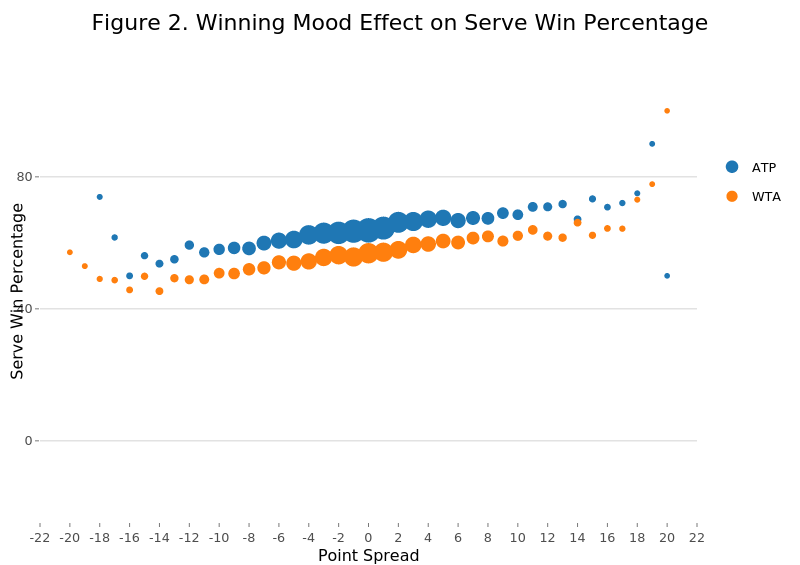

Figure 2 looks at how the average serve win percentage changes with point spread. It reveals a roughly linear and positive correlation that suggests the chances of winning a point increase with a positive point spread and decrease when the server gets behind in the point spread.

We have to be careful about interpreting this plot, however. Since we are just averaging over all points played at each point spread, it is possible that the quality of the mix of players at each point is changing in a way that could bias the result. For example, only the best servers might get to 10+ points ahead in the point spread and the worse servers get 10 points behind. So we have to adjust for player quality to truly assess whether a winning mood exists.

A mixed model is a natural way to account for quality and the clustering of points by server in the point-level data. In this model, winning a point is the outcome and we use random effects for the server and returner to account for the quality of the players in each match. The point spread is added as a fixed and random variable (for the server) to determine the server-specific impact the spread has after accounting for the quality of the players.

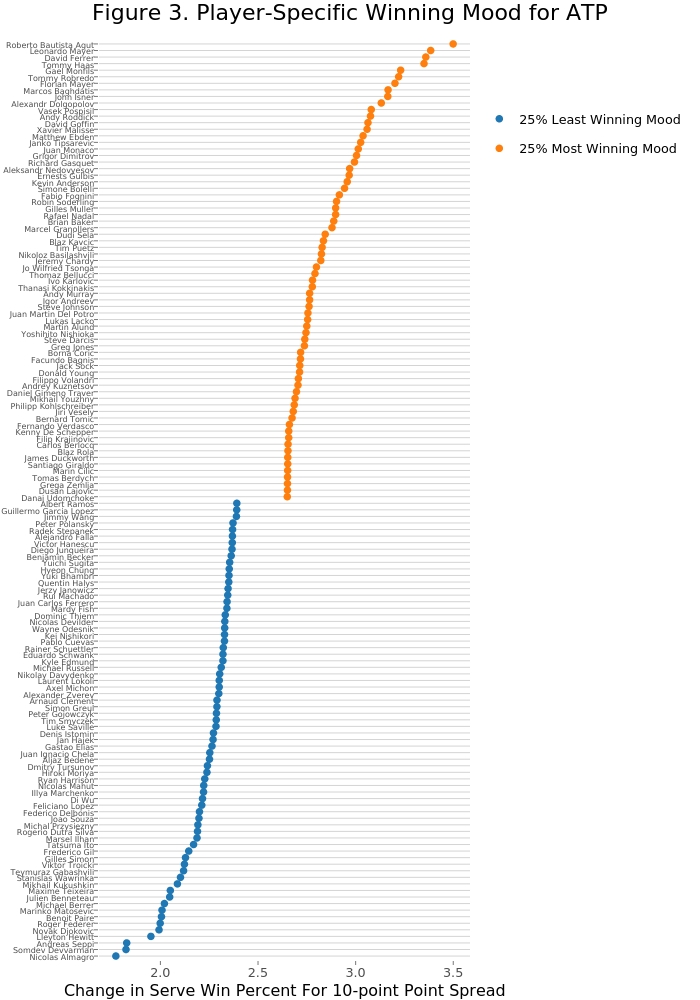

For the ATP, I found that the adjusted average effect of the point spread is 2.5 percentage points for every 10 points gained in the spread. Strong evidence of a winning mood. But keep in mind that the point spread effect is a double-edged sword because as much as a positive spread adds to a server’s win chances it makes it equally harder to win when the server gets behind.

Figure 3 shows the 25% of servers who are most affected and the 25% least affected by a winning mood. All servers are found to have a positive effect. Interestingly, we find Monfils at the 5th position, having a +3.2 percentage point effects for a +10 point spread. As I write, Monfils is in the first set of his Toronto Masters quarterfinal match against Raonic where the point spread looks to be quite close so far, giving him no extra boost of momentum so far.

Another interesting result from this analysis is that we find some of the most winning players in the least-affected group, with players like Lleyton Hewitt, Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic all clustered among the bottom 10. It seems that being too sensitive to momentum effects might not be a characteristic of a champion in the men’s game.

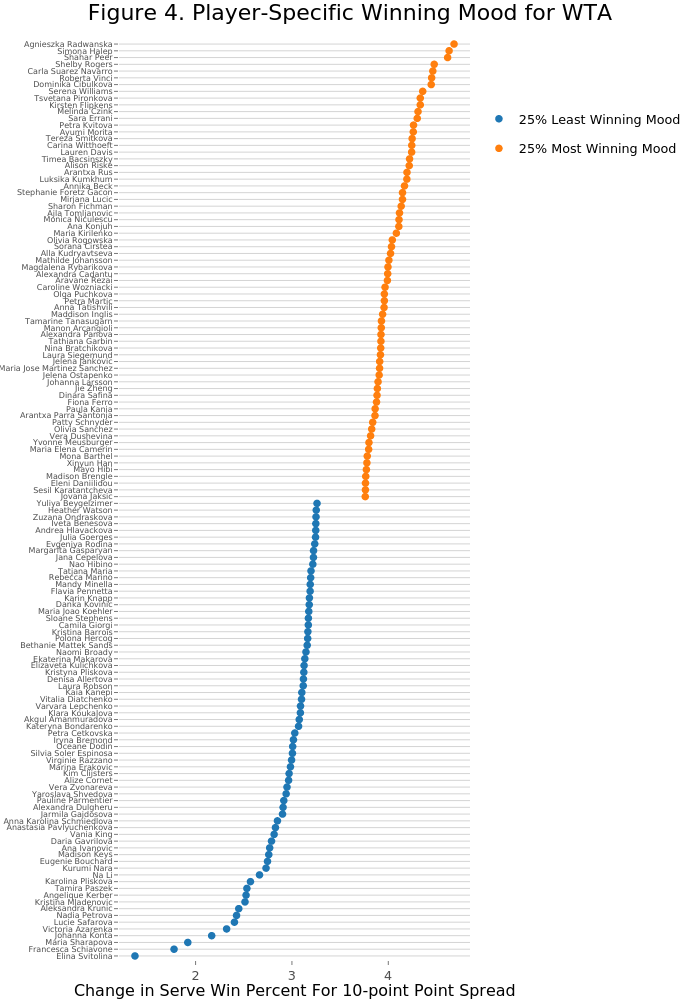

Bigger momentum effects are found among WTA players (Figure 4). Also, unlike what was found for the men, we find more of the best players among the players most affected by a winning mood. Players like Simona Halep, Serena Williams, and Petra Kvitova all have a greater than +4 percentage effect associated with point spread. On the women’s game, going with the momentum of the match is more of an advantage than a disadvantage, it seems.

Summary

Even after controlling for the possible bias of player quality, there is still strong evidence of a winning mood in tennis that can lift a player up when they are ahead but also make it harder to climb back when behind in the score. This not only points to a major effect of the mental game in tennis, it turns the idea of independent and identically distributed points squarely on its head.

Some other interesting suggestions from the analyses in this post are the player-to-player variation in effects and differences between the men’s and women’s tours. In particular, we find that the best players in recent years have been the least prone to winning mood effects, while the opposite appears to be true for female champions.

Winning mood not only appears to exist in tennis but it seems to be a gold mine for further study into the effects of momentum in elite sport.

If you liked this story, share it with your followers or follow this site @StatsOnTheT on Twitter.